Reflections on a multi stakeholder workshop in Botswana

By Daniel Morchain, ASSAR Co-PI - OXFAM GB

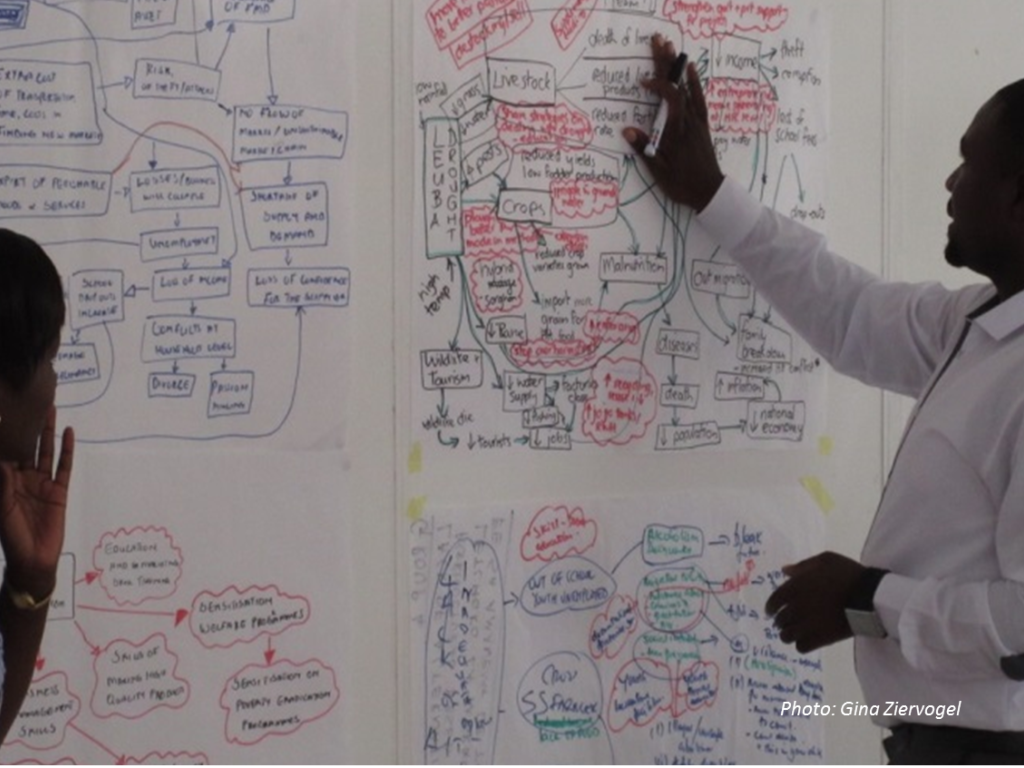

It was the worst-hit place in the country. A few days before the storm hit, and with temperatures teetering around 45â°C, a team from ASSAR – University of Botswana, University of Cape Town and Oxfam GB – ran a Vulnerability and Risk Assessment (VRA) with a group of approximately 20 stakeholders from Bobonong and the general Bobirwa Sub-District. This is not a typical vulnerability assessment, but rather, in the spirit of the wellbeing approach, it offers a holistic approach to understanding vulnerability, wherein key actors collaboratively design and implement programmes and resilience building initiatives.

The VRA exercise was designed to enhance our understanding of the vulnerabilities and capacities of social groups with respect to climate hazards and other issues, as well as to engage stakeholders in the design of adaptation responses. But after the two day workshop I think that all of us left with something more. That ‘something more’ was different for every person and, while as a whole the outcome of the VRA could be seen as contributing to a more focused resilient development thinking, I would claim that the personal gains were equally significant.

Unplanned outcomes

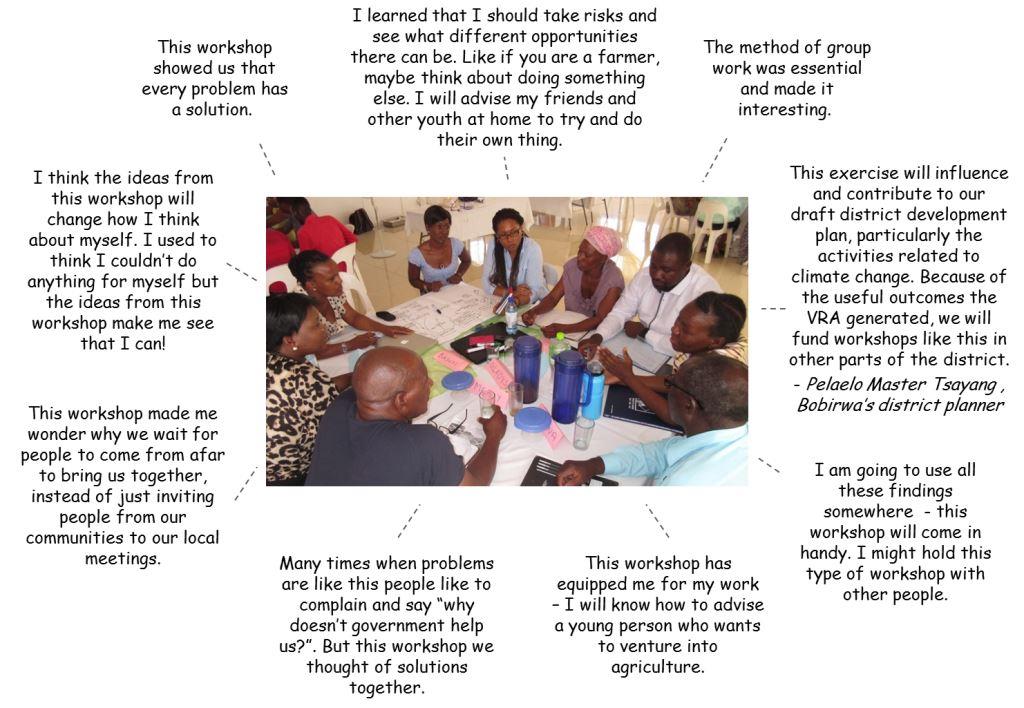

One important outcome was to shed light on and make accessible to the regular citizen the development work that government is doing, particularly around climate change. Creating this proximity among participants helped break barriers between officials and civilians.

“We now have a better sense of what areas the government is addressing here, and the gaps. I’ve learned about the priorities that the government has in this sub-district.”

“This exercise will influence and contribute to draft our district development plan, particularly the activities related to climate change. Because of the useful outcomes the VRA generated, we will fund workshops like this in other parts of the district.”

- Pelaelo Master Tsayang, Principal Economist and District Planning Officer, Bobirwa Sub-District, Botswana

Another outcome was the recognition of the value of people’s inputs, whoever they are, whatever they represent, as well as an understanding that every individual can contribute to processes that may, wrongly, seem or be framed as inaccessible to ‘non-experts’.

“I used to think my ideas weren’t worthwhile. Now I think I can make changes in my life and I know it is possible.”

- an elderly woman who makes baskets from Mokolwane reeds

“At the beginning of day one I didn’t understand why mophane worm harvesters were sitting around this table; now it is clear.”

“Now I see that even our field assistants have something to contribute, so we have to listen to them.”

A third ‘soft’ outcome of the workshop was recognition of the benefit of joint work and a push to proactively look for solutions to problems.

“I’ve learned I don’t have to keep waiting for the government to do something, but rather more proactively involve myself in finding ways forward.”

“People like to dwell on problems rather than focus on solutions. That’s not what we did here. That’s why I liked this workshop.”

“It was like a dream having the opportunity to sit around this group of varied people. When they contacted me on the phone to invite me to this exercise I thought this wouldn’t take us anywhere, but now I believe it will.”

“Having this wide variety of stakeholders sitting together as equals and coming up with joint ideas... this I found very humbling.” - Prof. Hillary Masundire, University of Botswana

Thinking about Research into Use (RiU) in ASSAR, CARIAA and in general in the development context, two things have stuck with me after the VRA in Botswana.

The first is the effect that being a part of something ‘big’ can have on people’s attitudes. This showed in a few ways:

- The openness of people to jump from a passive to an active state if pushed just a little bit.

- People’s willingness to see that agendas can and often need to have common objectives if they are to be long term and owned by many stakeholders.

- Certainly not least, the power of co-creation: passive, one-way interaction with stakeholders that focus on data extraction is short-sighted and doesn’t support a true, sustainable collaboration between governments or researchers and ‘vulnerable’ communities.

Active attitudes of stakeholders working together can lead to the development of climate change adaptation policy and practice that has positive influence across governance scales.

The second point that stuck with me after the VRA is the shift in perceptions that this kind of multi-stakeholder participatory process can trigger. Such as, how different kinds of knowledge can rapidly shift from being considered irrelevant to relevant. Also how people can take advantage of opportunities to move beyond the silos where systems and organisations have placed researchers, government employees and development workers, and to collaborate with each other.

While not all of these advantages can emerge from two-day workshops alone, honest and open stakeholder engagement with clear and realistic expectations is a good way to start. Other than that, I personally think there’s no magic; it’s just a matter of fairness, tenacity and working things out as people to find ways to make progress.