Reversing the culture of underplaying play

By Ritwika Basu

Three full days of games, fun and learning! The workshop on ‘Experiential Learning’ began on that note.

The idea was to use and learn to facilitate games of different formats to communicate complex ideas. Games were thought of as tools to break down barriers to conversation, demonstrate complex human behaviour, reasoning and individual temperaments, and potentially build an understanding towards solutions.

Our facilitator Bettina (Senior Learning Specialist at the Red Cross Climate Center) grabbed the opportunity to assemble a diverse group of researchers and practitioners working on the Adaptation at Scale in Semi-arid regions (ASSAR) project.

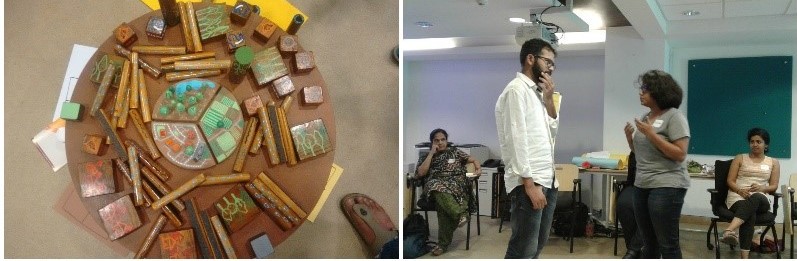

The Games

|

Each game was unique in the way it approached different aspects of a variety of differing elements: intellect, sense of ethics and morality, physical dexterity and individual and collective boundaries of comfort. Most importantly, it challenged the notion of work that’s often bereft of ‘play’. Each game urged us to let go a bit more. They created a sense of anticipation and urged us to maneuver in unknown terrains. Such insights are critical to adaptation, which is, after all a space where diverse actors, with competing agendas and different worldviews are trying to come together to work their way through complex issues such as climate change. |

To explain, here’s a list of games that touched on some of the aspects mentioned above:

-

‘Meet my daughter’- a game to introduce oneself through the eyes of another.

-

‘The third space’- it has multiple interpretations depending on the narrative, ideal for communicating challenges of working in large projects and teams (very apt for ASSAR). The game highlighted aspects of strategic coordination and contributions from all players.

-

‘Walk of Life’- a visually compelling and thoughtful game to illustrate complex concepts such as differential vulnerability, inequality, and power dynamics in a given context shaped by scenarios narrated by the facilitator.

-

‘Paying for Predictions’ and ‘Seasonal Forecast’- Two very exciting games with elements of gambling, competition, individual and collective rationalisation of resource use shaped by varying degree of uncertainty, and decisions linked with risk aversion. The narrative of disaster risks linked with climate change forcing communities to consider to differential costs characterising anticipatory versus post disaster responses made it highly relatable to our project.

-

‘Tipping point’- A game modified by ATREE to effectively demonstrate critical dynamics of delicate socio-ecological systems, such as in their study site in Moyar-Bhavani region. The underlying principle as the name suggests is that of ‘balancing the system’ following a ‘systems approach’. As the game proceeds, it proves to be quite instrumental in facilitating discussions around resource mobilisation and tradeoffs, competitions and externalities, balance and innovation.

In addition, games like ‘The elevator pitch’ and other propped puzzle games, motivated players to exercise their negotiation and communication skills to maximise influence through imagination and role play.

We learnt to toy with an array of narratives, possibly adaptable to our work on adaptation in India. We even brainstormed and played with the underlying mechanics of some games. By playing the games ourselves, we encountered emerging innovations around game mechanics, and collaboratively worked in groups to contextualize them to our study regions and themes. After the first few attempts at combining different narratives with interesting mechanics, we gradually got tuned to the playful dimensions of games, while, simultaneously deriving key messages that each game intended to convey.

Collective reflections

Post-game reflection sessions, apart from gathering individual thoughts around each game, also unearthed important insights and tips on facilitation, content, and time management. We realised that for the workshop to be truly participatory, the workshop design and execution must make the participants feels safe. Thus, alongside innovation and technical aspects of game design, equally important for the facilitator, is to acknowledge cultural and regional differences, and embrace participant sensibilities. It is important for the facilitator to sensitise the group early on in identifying and respecting boundaries set by individuals. Facilitators must also acknowledge existing incompatibilities and power relations in non-homogenous groups. This is crucial for the facilitator, prior to any attempts to neutralise the effects of such differences in the team, to ensure increased effectiveness of participatory processes such at this (Read here more on Facilitation and Diversity).

Going forward

By the end we all agreed there were unique opportunities presented by a mix of innovative light-hearted games in mobilising difficult conversations. Games, in that sense are ice breakers. Furthermore, they are crucial in shifting discussions from passive observers’ perspectives, to inputs arising from lived experiences, even if drawing from a simulated environment. This is useful in bringing to life content and context, that are far removed from the reality of participants.

We found this medium effective. It enabled cross-learning, allowed us to contest, agree and disagree. The platform drove thinking towards some of the embedded yet resolvable challenges of consortium based multi-disciplinary, multi-locational projects that display a diverse composition of ideologies, skills and orientation. Conversations on climate change adaptation that involve competing stakes, diverse views, and an array of differentiated outcomes affecting a range of advantaged to disadvantaged actors over temporalities, proved to be quite a pick for testing out games as a medium. Going forward, ASSAR intends to integrate such methods with conventional forms of research.