Attempting to transform the future – reflections from the TSP process in Bangalore

By Prathigna Poonacha - Researcher, Indian Institute for Human Settlements

Water in Bangalore is in crisis. Multiple issues plague this water system, including trying to meet the ever-increasing water demands of a growing population. There is pollution and contamination – of ground and surface water. There is also the problem of encroachment and mismanagement of lakes and storm-water drains resulting in urban flooding at every extreme rainfall event.

These issues are not new to the city and many configurations of solutions and interventions have been tried.

· Civic authorities responsible for water supply are trying hard to tap into newer sources of water for the city.

· Many citizen groups are initiating action around lake restoration, rejuvenation and management.

· The government recently cracked down on much of the encroachments on storm-water drains in the city.

· Rainwater harvesting has been mandated for all buildings under law.

Yet, the scale of these problems requires coordinated action, as piecemeal solutions do not provide substantial relief.

The truth is we are stuck! A systems approach is required to understand and address the water problems of the city – an approach that recognises how natural and social systems work together.

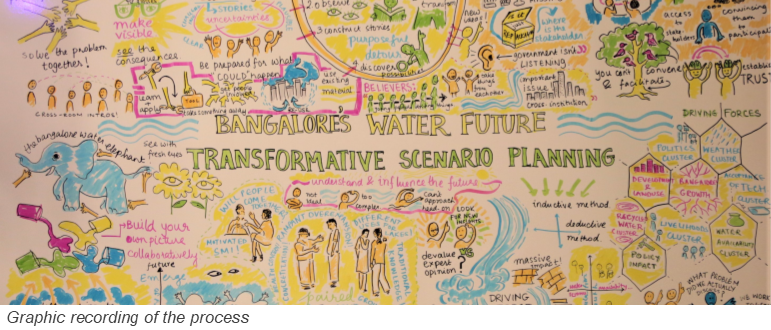

The TSP process offered us a method to think through this problematic situation using a systems lens. It also offered us the opportunity to bring the multiplicity and diversity of water stakeholders together in conversation with one another, to identify important drivers of this problem and then to work together towards transformative futures for the city.

The TSP process was undertaken by the Indian Institute for Human Settlements (IIHS) for a period of almost 18 months and is still ongoing.

It included three workshops. The first was a training workshop held in October 2016 to understand the TSP method and the appetite for such a process among water stakeholders in Bangalore. The second and third were part of the actual TSP process. The workshops were titled ‘Water and you – Bangalore’s future?’ and held in July and December 2017 respectively. We engaged with more than 25 stakeholders from the government, academia, non-governmental organisations, private sector, citizen and community-based groups.

As organisers and conveners of the process, it was a tremendously enriching experience for us. But the process was not without its challenges. I reflect here on the top three challenges we faced in the course of this journey:

Getting the right people in the room

(Who convenes the process?)

While TSP offers a lens to think systemically around an issue, it is important to bring people into the room that represent the entirety of the system. In our case, it included representatives from government, academia, civil society, media, the private sector, businesses, activists, and so on. However, getting the government officials into the room, many of whom were the most important stakeholders, was a challenge for us. There are multiple government institutions who are stakeholders of the water system in Bangalore. While we invited almost all institutions to participate in the process, either there was a lack of interest on their part or a lack of time to participate. It is important to note that a lack of capacity (both in terms of numbers and ability to engage) is a serious governance issue in our context. I think some of this has to do with who we are as an institution convening the process and I hazard a guess that we may have had much more participation had we been another government organisation.

In terms of participation from other groups, though, such as civil society or academia, we had a good response as IIHS is regarded as a neutral space for difficult conversations.

Time-consuming process

A full TSP process is run over a period of 24 to 36 months. In the ‘lite’ version of TSP adapted for ASSAR, we took about 18 months to conduct three workshops. Engaging the same set of stakeholders for such long periods of time is particularly challenging, especially where ‘once-off, one-day’ workshops are the flavour of the day. This requires serious and sustained commitment from both the participating stakeholders and the organisers. In this process, it is desirable to have the same set of stakeholders attend both the workshops. In our second workshop, we had about half the number of participants who attended the first one. Ensuring that most participants attended the second workshop was challenging given that many of them prioritised other commitments over this. As a result, the continuity and engagement with the process as well as the depth of relationships among stakeholders was diluted.

What next?

(Self-transformation is not enough! We need tangible and perceivable outcomes)

The TSP process offers transformation in five areas as its outcome: a) Language, b) Understanding, c) Relationships, d) Intentions, and e) Actions. It proposes that transformation in the first three areas causes a shift in participants’ will to act (intentions) in a stuck situation and therefore transforms their abilities to act and better the situation. The second day of the second and last workshops ended with stakeholders voicing the actions they would like to take in order to realise the desired future they had articulated in the course of the process.

But many in the group later expressed that after the lengthy TSP process they would have liked to see some tangible action in the present, rather than the possibility of action in the future.

Perhaps this shortcoming would have been partially addressed had there been better representation of government, since government has the agency to decide and implement some of the recommendations that were made by the other stakeholders. This articulation, however, also reflects a tinge of frustration among stakeholders about an ‘all talk and no work approach’, and points to the urgency of the situation.

Finally, for us as convenors, this experience is full of richness and learning, despite any shortcomings in the way we put it together.

The most important takeaway is that the TSP process is only the beginning of what needs to be a long and deep engagement on the issue of water in Bangalore. All stakeholders need to be on board, if we are to realise a desirable, sustainable and liveable future for the city.

This article first appeared in the March 2018 ASSAR Spotlight