Stakeholder engagement event sparks lively discussions in Mali

Reflecting on work done and charting the course for the work ahead: ASSAR’s West African team meets with district-level stakeholders in Mali

Written by: Amadou Sidibé, Kadiatou Touré and Tali Hoffman

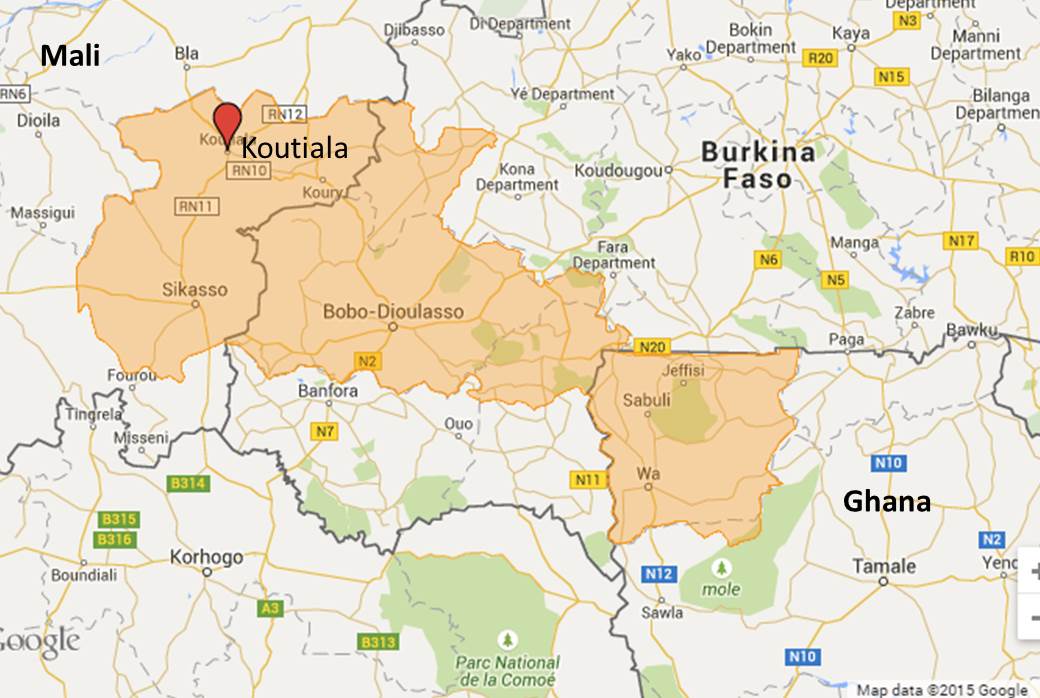

In July 2015, members of ASSAR’s West Africa team held a stakeholder engagement event in Koutiala, Mali as the first step of a sequence of multi-scale communication and feedback sessions about their Regional Diagnostic Study (RDS). The aim of this event was to share the RDS findings with local stakeholders, and to accommodate stakeholder comments and suggestions as the ASSAR team prepares to transition from the RDS phase to the next phase of ASSAR: the Regional Research Programs (RRP).

This event brought together 16 stakeholders from the district-level (some returning, some new) including CCAFS members from four villages (some of whom were farmers), technical staff from NGOs, and researchers.

Reflecting on the findings from the Regional Diagnostic Study

The team stressed that the effectiveness of future adaptation efforts requires more knowledge of climatic and biophysical factors, socio-economic factors, cultural factors and political and governance factors. However, they revealed that the effectiveness of past adaptation efforts in West Africa had been most greatly constrained by key factors, including governance, development, and gender.

Governance

In terms of governance, the team explained how the major constraints identified in the RDS were:

- The incomplete government decentralization: transfers of authority to local governments have been ineffective.

- Top-down policy interventions for managing natural resources that lack local incentives and lock local communities out of resource access.

- The lack of land tenure security that demotivates land users to adopt new practices.

- The traditional land tenure system that marginalizes smallholders.

- The lack of communication and coordination within national level institutions and across national to district scales.

- Ineffective mechanisms or funds for implementing national adaptation policies.

Development

The team also detailed major development constraints identified in the RDS:

- The lack of integrated land management and water resource planning.

- The high dependency on donor communities for funds to implement adaptation projects.

- The extensification of agriculture onto the drought-prone soils and grasslands used primarily by pastoralists (thereby reducing access to pastoral corridors and generating herder-farmer conflicts in many regions).

These constraints resonated with the stakeholders present at the meeting, and a conversation between two stakeholders highlighted how well-intentioned development efforts can be maladaptive (more harmful than helpful). One participant from described how his NGO’s efforts to manage groundwater had failed in the past. He said that they had invested CFA 60 million (West African francs) to build a dike (a wall to regulate water levels) in the village of Fignesso (located 30 km from Koutiala). By improving the availability of water for crops and livestock the dike had the potential to generate CFA 260 million annually for the village. However, to his dismay, the village failed to invest the CFA 20,000 needed annually to maintain the dike. Another stakeholder, also involved in this project, responded to this, saying that the villagers failed to pay this annual fee because the dike didn’t meet the expectations of the farmers. He explained that the dike led to the upstream crops rotting underwater, while the downstream crops failed because of water shortages. He said that no technical measures were taken to ensure that water from the dike was equally distributed among farmers.

Gender

The ASSAR team also explained how the major gender constraints identified in the RDS were:

- The high labour burden of women and the lack of female access to education that constrain women’s ability to diversify their livelihoods.

- The limitation of livelihood and/or technologic options for women that constrain the range of responses for managing risk and adapting to change.

- Traditional gender norms that manifest in unequal access to production resources and decision-making processes.

- The predominance of male migrations that leave vulnerable groups, including women, youths and disabled dependents exposed to shocks, particularly where remittance flows are weak or missing.

The concept of gender acting as a barrier to adaptation invited enthusiastic responses from the stakeholders at the meeting. These responses initially centred on the different ways that women are viewed in this society.

One civil servant was adamant that women are marginalised in relation to development outcomes, and that the interests of women should be better accommodated in development processes. He added that women are discriminated against in terms of access to education, citing the much higher rate of boys’ enrolment in schools compared to girls.

Another stakeholder disagreed, saying that women have always played a pivotal role in society, one that stretches from involvement in agricultural production systems to influence in household decision-making. The latter, he said, is encapsulated in local expressions such as “the night bears advice” and “the night is rich in teaching”, which refer to moments when – unable to resolve issues on their own – men consult with their wives at night to aid their decision-making the following morning. He believed that – although cultural differences may create the perception that women are marginalized in some societies – the role of women is considered important and recognised in every society, and added that, to avoid bias and controversy, cultural differences must be properly understood before gender agendas are set.

Discussion then moved beyond male/female disparities to take into consideration all of the vulnerable social groups subsumed by the word ‘gender’, namely youth, elders and disabled people. Participants felt that of these categories, the youth need in Koutiala need particular attention. They agreed that the younger generation is less and less motivated to farm, and is reluctant to follow the tradition of abiding by the decisions of family elders. This change in behaviour has negative consequences for both agricultural production and the family dynamic.

Transitioning to the Regional Research Programs

Once the RDS findings had been discussed, the ASSAR team shifted their focus to planning the way forward for the RRP phase. They asked stakeholders to identify the research topics that they found relevant for climate change adaptation in Koutiala. These topics were generally focused at the nexus of intensification and adaptation, and included:

- The need for improved groundwater management so as to minimise the dependence on erratic rainfall for agriculture and livestock husbandry.

- The declining motivation of young people for farming activities, a change that affects the organisation, decision-making structure and cohesion of families.

- The role of the government in adapting national-level rules and regulations to local-level realities and cultures.

- The communication gap that exists between the local and national scales.

- The communication gaps that exist between different stakeholders, including researchers, farmers and decisions makers.

Conclusion

The meeting’s lively debates and discussions suggest that the district-level stakeholders truly engaged with, and internalised, ASSAR’s RDS findings. The discussions also brought particularly pertinent issues to light. The issues discussed around women and youth, and their implications for family dynamics, indicated the relevance of the social differentiation and gender dimensions of ASSAR’s RRP. The case of the dike, with the contrasting perceptions of donors and farmers, highlighted that intensification measures that are ill-designed or not aligned with farmer’s needs, can lead to adaptation efforts that are more harmful than helpful. Finally, the questions around the role of the state and communication gaps between governance scales, confirmed the importance of investigating how governance, political and institutional issues either enable or constrain adaptation processes.

By deepening the understanding of these issues in Mali and Ghana, the RRP phase is likely to inform processes at the intensification-adaptation interface in West Africa’s complex development context. By ensuring that the RRP – and in particular, its Research into Use component – is framed around the practical needs of vulnerable farmers, ASSAR may also help to achieve long-term and sustainable stakeholder engagement in the region.