Rural inhabitants ask for village-level ‘water use management’

By Marcella D’Souza, Eshwer Kale and Hemant Pinjan, Watershed Organisation Trust (WOTR)

This article shares the experience of how Transformative Scenario Planning in the district of Jalna in Maharashtra, India motivated people for action on water management.

Jalna district in the Marathwada region of Maharashtra has in the past decade been facing recurrent droughts. Here, the majority of the rural inhabitants (i.e. approximately 47%) depend on agriculture as a source of livelihood. With expanding agriculture, farmers are increasingly dependent on groundwater to sustain farm productivity. While the groundwater levels are declining, recent assessments show that the water levels have dropped between one to three meters during the past 5 years. Reduction in rainfall and increasing dependence on groundwater requires better water management practices to sustain agriculture in a changing climate scenario.

THE TRIGGER: The Transformative Scenario Planning (TSP) exercise in Jalna district took place between June 2017 and February 2018 on the topic:

“The water situation in rural Jalna in 2030: for domestic and livelihood needs.”

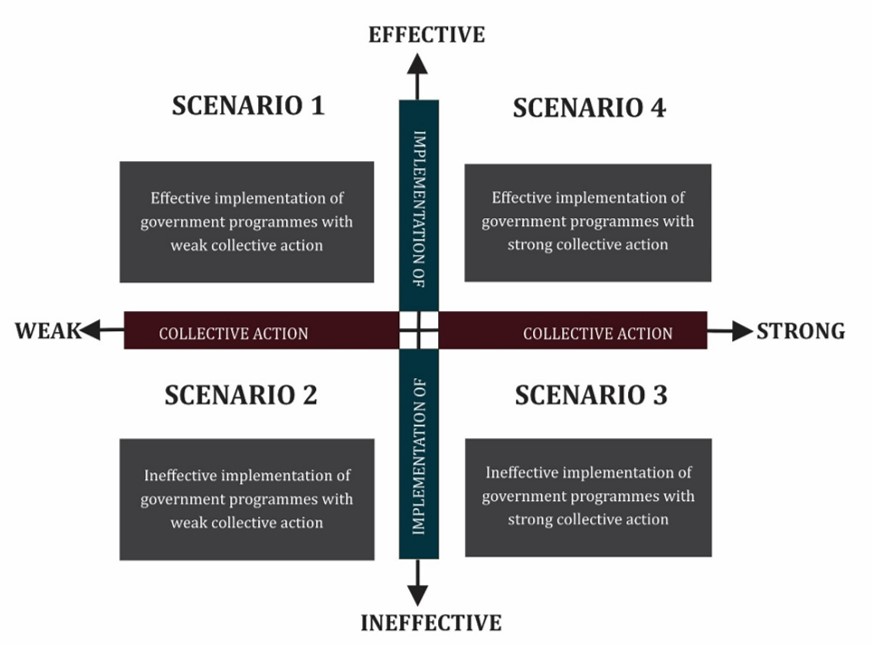

The participants from various blocks of the district represented stakeholders of all landholding categories, including landless poor, women, academic institutions, small industry, local NGOs, government officials and college students. Villagers from Jaffrabad and Ambad blocks of Jalna district also participated. In the course of the TSP exercise the participants identified two major drivers that have a high influence on the current and future water situation: 1) Collective action and 2) Implementation of government programs.

Each quadrant was then developed into a story. While wading through the stories of the four scenarios, participants identified the “opportunities” and “threats” that contributed to the realisation of each scenario. They drew insights from these and then created a scenario of the “desired future” for the “water situation in rural Jalna in 2030: for domestic and livelihood needs”.

In order to achieve the desired future, participants analysed their actions regarding water use in daily life and discussed (i) Actions which ought TO BE DONE; and (ii) Actions that are TO BE AVOIDED.

Water literacy and groundwater management emerged in many statements. This sparked the idea of implementing a capacity building exercise with gram panchayat members and village representatives in 20 villages in Ambad and Jaffrabad blocks where 101 persons participated, including 37 women.

A MINI STEP TOWARDS REACHING THE DESIRED FUTURE IN RURAL JALNA IN 2030

As described above, given that Jalna has been facing frequent droughts in the past decade, groundwater management is crucial. Falling rainfall levels, together with an expanding area under agriculture in a region where 47% of rural households are farmers, drives people to exploit groundwater to meet the growing farm-based livelihood demands.

Capacity building activities included sensitizing participants regarding the increasing scarcity of precious freshwater due to both climate change (increasing droughts) and anthropogenic action. Discussions, short films as well as experiential learning (Common Bucket Game), proved to be an eye-opener to the participants as a group.

The discussions, film and games motivated participants to analyse the ‘water health status’ of their villages: the signs and symptoms of a village’s water health, its causes and socio-environmental impacts. The film on water budgeting “Goshta Paani Niyojanachi” encouraged participants to learn about and prepare a water budget for their respective villages.

On returning to their respective villages, the motivated gram panchayat members and other participants shared their experiences with their communities and encouraged them to take action.

PARTICIPANTS COMMENT ONE-AND-A-HALF MONTHS AFTER THE TRAINING ON WATER STEWARDSHIP AND WATER BUDGET PREPARATION

Mrs Saraswati Raut of Mardi village, Ambad block in Jalna: We definitely need to do water budgeting in our village – one hundred per cent!

Currently we have enough water for domestic needs. We don’t have to walk far to fetch water anymore since WOTR started watershed development in our village four years ago. Before this, during the summer months, water was brought in by tankers and if it was not sufficient, we would walk for one to two kilometres to fetch more from private wells. Our bodies ached; we had no time to take care of our children.

In the training, I came to know about the importance of water and that ‘water is public property, and everyone has a right over it’. Many people think water is their private property; they think ‘water under my land is my property’. However, few of them think that God has ownership over water. In the training we were taught that water belongs to all. We learnt how to save water and recharge water into the ground. We played a game where water from a pot was lifted through straws by four groups, with each of them competing to take out more than the others. We also got information on the 2009 Groundwater Act that has become implementable since 2014.

If people come together, we can make rules for water use in our village. Our concern is that we need to limit the number of borewells in the village. The increasing number of wells will result in making a sieve of our land! Borewells should not be drilled beyond 200 feet and micro-irrigation would have to increase. However, all villagers have to come together to discuss and plan the water budget; suggestions of all villagers need to be heard in taking decisions. If people come together, rules can be made in the village on water use. But at the same time, negative thinking in villagers is what prevents people from coming together and taking actions on water budgeting.

But if we prepare and follow the water budget, all women will be able to save their time and labour, and they can spend that extra time on their own. We will be able to complete our routine work without any hurdle of unavailability of water.

Mr. Limbaji Kannar, gram panchayat member of Aadha village in Jaffrabad, Jalna:

Earlier, in our village Aadha in Jaffrabad block, the river flowed even in the month of May and water was available in our wells. Then, from the year 2000 onwards, the number of borewells increased and water extraction resulted in water scarcity forcing people, particularly women, to fetch drinking water from one to two kilometres distance. However, since the ‘Kolhapur Type’ (KT) weir was constructed on the river and compartment bunds were implemented on farms (around the year 2010), the water situation has slightly improved. But even now, women and the elderly are forced to spend time fetching water from a distance between the months of March to May. Children often spend time during school examinations fetching water. To address water scarcity, a few years ago we dug another well for drinking water purposes and have provided tap connections; yet from the months of February to May water is provided once every three days. We also have a reverse osmosis plant for drinking water, which is made available at a cost of Rs 5/- (US$ 0.071), for 15 litres.

In the training on water stewardship we became aware that underground water is limited. We learnt how to calculate the water stock and measure the rainfall in our village, as well as how to make water-use plans for the village. We also learnt how we can increase water availability by repairing water harvesting structures, and to manage water use for agriculture. For the first time in my life I heard the word ‘water budget’ in the training given by WOTR. Water budgeting is an important process; it is similar to the process we follow when arranging a marriage ceremony in the family. The budget is planned and the expenses are managed within the budget; we ensure an efficient use of the money allocated. I learnt how to calculate the water available; which crops require less water; the loss of water as runoff and evaporation; of groundwater and water harvested in storage structures. I learnt which crops to take when rainfall is little, and if there is good rainfall how to harvest more water in the village. Thus, I observed that for a village, ‘water budgeting’ is a very necessary process that needs to be applied. I even came to know that participation of all villagers is necessary to implement the water budget at village level.

After the training we discussed the water issue in our village gramsabha (village general body meeting); however we need to motivate the people a lot more so that the water budget can be prepared regularly. People’s mentality of ‘not accepting change’ is a real challenge. People don’t change their behaviour and practices very easily. People also fear that they will lose their existing share of water because of water budgeting. It is difficult to shift people out of their perception that ‘to the landowner belongs all water below their land’ to the idea that ‘groundwater belongs to all’. Even in applying the water budgeting process we will face the challenge of village-level politics, where there are different groups and subgroups who always take an opposite stand to each other. Hence bringing all to make decisions in consensus and take action on water budgeting is a difficult task. Besides, most people are more concerned about the immediate benefits hence it is difficult to mobilize them for long-term water security and water for all.

In order to implement ‘water budgeting’ in our village, we need to motivate the people by inviting leaders of villages where the water budget is being successfully implemented. We need to have exposure visits to these villages; show videos and have street plays to spread the message that water budgeting can be very effective for our village. Besides these, forming a committee and installing rain gauges and a weather station will also help. We plan to start the ‘water budget’ process on October 2nd 2018 on the occasion of Gandhi Jayanti.