Adapting to what? Reflecting on multiple drivers of change and response strategies

By Ahmed Khan, PhD.

Ahmed is a foodie and recipient of the 2017 IDRC Professional Development Award. In CARIAA, he is interested in cross-consortia synthesis and communication tools. His broader research interests are on environmental governance and the human dimension to global change. His work has been featured in journals such as Ambio, Bioeconomics, Climate Policy, Fisheries Research, Regional Environmental Change, and Science

Red Red, a staple cuisine in Ghana (Photo: P. Adiku)

Plantains and red beans cooked in palm oil on a bed of minute cassava flakes or ‘gari’ are unique cuisines to Ghanaians. This delicious dish called Red Red can be served at breakfast as well as lunch depending on appetite (Photo 1). Although plantains by themselves (and beans) are a common staple food in Western Africa and even beyond, they are not often prepared and sizzled together to produce this nutritional richness. So, having Red Red once a day (and goat soup on the side) was one of my highlights at this year’s meeting of the Adaptation at Scale in Semi-Arid Region (ASSAR) research consortium.

ASSAR is one of four consortia designed and funded to explore adaptation strategies and build capacity in climate change hot spots under the Collaborative Adaptation Research Initiative in Africa and Asia (CARIAA). Granting that this is not my first time in Ghana nor to a climate change adaptation conference, I had this feeling of déjà vu about conversations around the complex linkages between climate and development (and its implication to food systems). The last time I had such a privileged dialogue was in Negril in April 2014, but this time instead of Red Red, the conversation was over Jamaican Patties and Jerk Chicken.

The question that has been nagging me all this time is: “what are we adapting to?” Knowing that climate change is cross-cutting and may interact with other global drivers to affect various ecosystem services and undermine human well-being, one can argue for integrated responses towards global change (both environment and economic change). Despite so many insights emanating from global change research, the driver-impact-response relationships are not often linear or straightforward but rather complex, which make correlation and causation ambiguous and imprecise. Hence, the tools for adaptation planning and intervention are not too different from natural resource management or rural development. How then can we identify complementary responses between climate and development challenges?

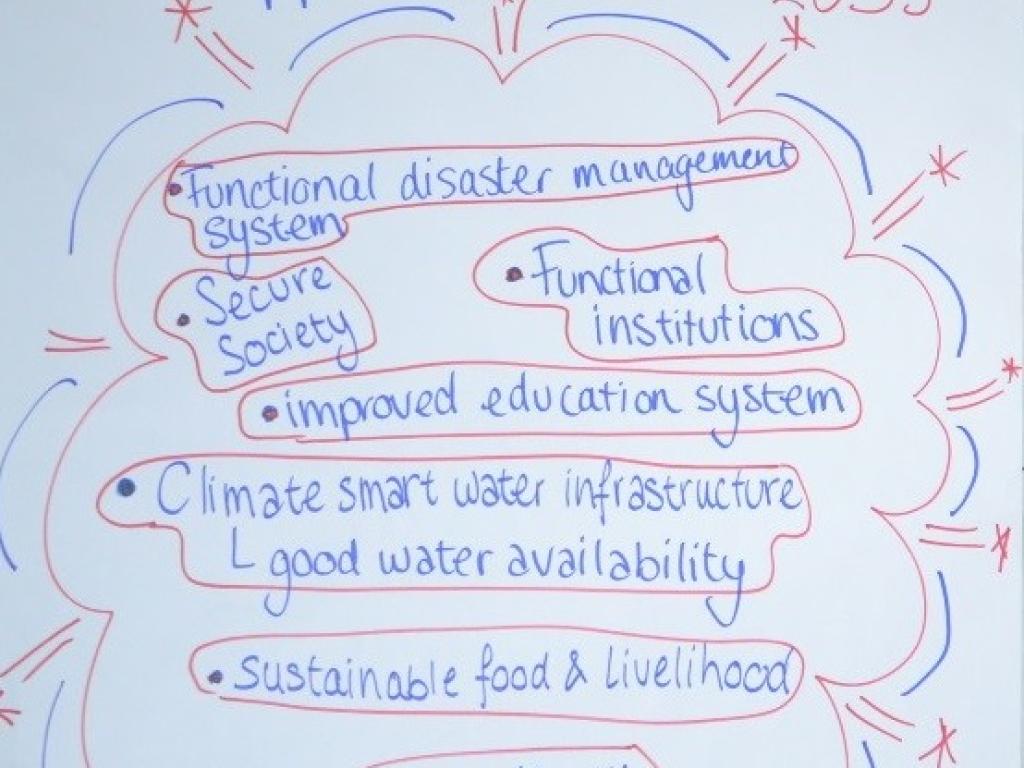

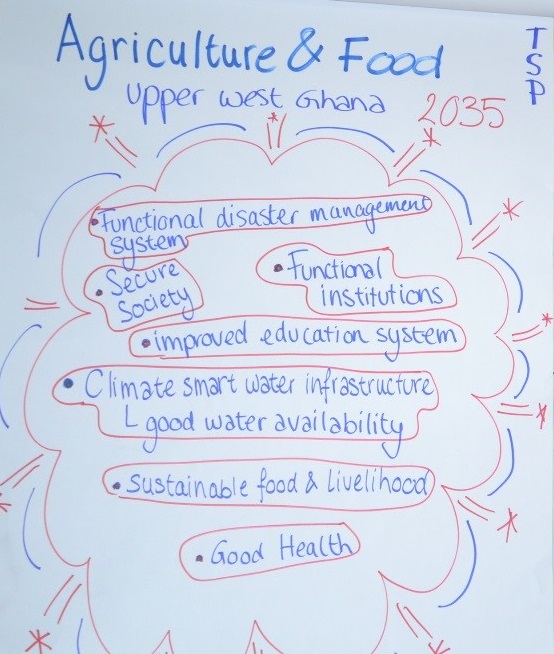

I think the key strategy is to ‘frame’ the climate problem broadly and to search for entry points or windows of opportunities to meet multiple objectives relating to global and local drivers of change. Whilst some adaptation interventions are forward-looking by mitigating disasters and future risks relating to climate hazards, others can be reflective, focusing on new ways of governing, for instance strengthening land use plans and adopting new forms of climate-smart agricultural practices. In this context, maintaining Red Red as a staple in Ghana in the light of climate change requires policy reforms in food production but also to the interplay of agro-ecosystems, livelihoods, and institutions. Flooding and drought are seasonal events that affect food production in Ghana (Photo 2). With climate extremes, prolonged droughts can lead to multiple concerns beyond food security such as land use cover change, migration, conflicts over resource access, and disenfranchisement. Thus, strategies towards food security under extreme climate scenarios must account for multiple interventions and target diverse sectors (Photo 3).

A farm vulnerable to prolonged drought in Northern Ghana and flood zones in the Delta Region (Photo credit: Courtesy of the ASSAR and DECCMA research teams)

These global challenges have been the focus of four research streams in ASSAR, namely: Ecosystem Services, Social Differentiation, Governance and Knowledge Systems. ASSAR’s framework and theory of change speaks to a variety of potential interventions, but it also relies on cross-regional learning and capacity building in vulnerable drylands in four regions spanning two continents (Asia and Africa) and in eight countries (India, Ghana, Mali, Botswana, Namibia, Ethiopia, Tanzania and Kenya). What was remarkable about this week-long meeting was the adept framing of the dynamics and cross-scale linkages in semi-arid climate hot spots and the design of research methodologies to reflect on these multiple drivers of change. At one end of the spectrum, you have household surveys that interrogates wellbeing, livelihoods and gender dynamics at the community scale; at another end, you are looking at transformative scenario planning (TSP) with nation-wide stakeholders, as well as simulation modelling on 1.5 to 2.0oC temperature increase.

Visioning for food security in Upper West Region by ASSAR researchers (Photo credit: P. Adiku)

Undeniably, focus on scale opens up cans of worms on methodological rigour, but it also offers fruitful research outputs and high impact on policy and practice. For starters, the range of knowledge outputs so far comprises of the traditional and formal research reports and journal articles as well as informal photo stories, briefs, videos, cartoons and blogs.

It was interesting and inspiring to witness cross-scale learning amongst researchers in over 10 institutions and various community partners such as START, Oxfam, and ATREE. The Stories of Change, an evidence-based narrative of impact, was the most moving. Remarkable examples included students who secured travel grants for short-term visits and mentorships to other institutions and the successful nominations of researchers honoured to be on IPCC working groups. I also enjoyed the evening games of table tennis and football (i.e. soccer), and the lively musical jamboree. These social events provided downtime to build relationships with colleagues, share experiences, and discuss career plans beyond CARIAA.

On my last day, en route to Accra from Akosombo, I reflected on the last session that I attended with Mark New (Principal Investigator for ASSAR) on desired outcomes. The ideas generated from the round table bode well with CARIAA’s theory of change, which is built on evidence-based outputs, wider spheres of influence and policy uptake, and local and regional impact.

At the end of it all, I embraced one of Wole Soyinka’s popular quote “…..the best learning process of any kind of craft is just to look at the work of others”. Indeed, I learnt so much from ASSAR colleagues, and I earnestly look forward to the next CARIAA meeting at Adaptation Futures 2018 in South Africa.

Read the original blog here