Pastoralism under pressure in the drylands of East Africa

By: Daniel McGahey, Regional Director - INTASAVE Africa

Over the next 50 years the semi-arid regions of East Africa are expected to become hotter with more wet extremes. Changes – including increased frequency and intensity of droughts and floods – are predicted to negatively impact food security, economic growth, infrastructure, human health, and wildlife and ecosystems. Over the last 50 years temperatures in this region have already increased by an average of 0.16â°C per decade – which is five times higher than temperature increases observed over the last century. Drought and flood hazards are expected to intensify demand for food, water and livestock forage. There has already been an increase in the number of climate related disasters in the region and between 2000 and 2006 these disasters affected almost two million people per year on average.

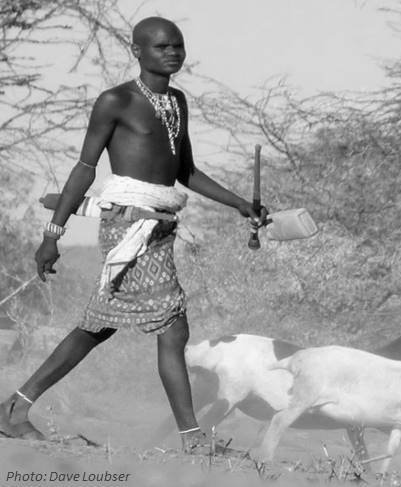

Typical of many landscapes in Africa, northern Kenya’s semi-arid region is a vast, open, largely unfenced grazing system occupied by numerous pastoralist groups and their livestock as well as agricultural communities. The latter typically settle on the higher areas of the region where rainfall is often greater, such as the foothills of Mount Kenya. People within this landscape are becoming increasingly vulnerable to climate change as a variety of factors such as land degradation, land fragmentation and an erosion of community-level norms around rangeland governance combine to reduce the movement of livestock, which further aggravates land degradation and increases conflict over grazing land and water. Climate stressors combined with these existing challenges, place increasing pressure on pastoralists and farmers alike.

Pastoralists have transitioned over the last 50 years from practicing a diversified livestock system (involving mobile family units keeping cattle, camels and small livestock) to increasingly commercially-orientated camel and goat production. This adaptation has dramatically changed the household economy as many people become more sedentary and engaged in localised livelihood activities, and contract herders are frequently employed to tend to more mobile camel herds.

We need to explore more closely the ways these transitions hav

e affected people’s wellbeing and consider the longer term implications under a changing climate. Early indications suggest that relational and subjective aspects of wellbeing have changed dramatically.

While people still perceive livestock ownership as the ultimate symbol of wealth, increasingly entrepreneurship and waged labour are equally prioritised. Women, especially, now engage in a wide range of localised trading activities from camel milk trading, goat marketing, and water and firewood sales, and therefore the most successful people maintain complex relationships with a diverse network of actors.

Traditional safety nets based around pastoral customs are increasingly rare as the vulnerable become more reliant on church-based support or the support of neighbours in peri-urban areas and larger settlements.

Our focus

In many ways ASSAR is breaking new ground in our quest to gather the knowledge East Africa requires to effectively plan and catalyse the sustained, widespread adaptation urgently needed within semi-arid drylands. To date we have been overly reliant on a series of simplified social vulnerability assessment tools that have in many ways failed to enhance our understanding of these issues. Through intensive fieldwork in northern Kenya the ASSAR East Africa team plans to build understanding of ways to improve people’s wellbeing under progressive climate change. We are specifically focused on the ways that climate change affects wellbeing through its impacts on agricultural production within farming and pastoralist communities.