Copious rain, climate change and co-learning: A report of the stakeholder engagement event in the southern Moyar, India

By Johny Stephen, Divya Solomon and Milind Bunyan with inputs from Shrinivas Badiger and Jagdish Krishnaswamy

Dramatic images and horror stories of the devastating floods found their way to news outlets and social media both in Tamil Nadu and across India. Words and phrases such as El Niño, extreme precipitation, climate change, and flood management suddenly became very common in the everyday narratives of the citizenry of Tamil Nadu. While the cause of this disaster could be a topic for another blog, it brought out human resilience in the face of adversity. With the government machinery overwhelmed by the scale of disaster, it was the common man who stepped up to the task, risking all to rescue and provide relief.

With the Chennai floods in the backdrop, we conducted our stakeholder engagement event in the southern Moyar region in the second week of December 2015. The build up to the meeting started in early November with Revathi contacting the various villagers in the southern Moyar region and beginning the task of mobilising them. The participants of the first stakeholder meeting were impressed by the way in which it was conducted. They had often been to meetings where they were lectured at, or were made to be seen as beneficiaries. This was the first time they were actively involved, and they were happy. The success of the first stakeholder meeting had spread quickly and people from other villages were eager to participate in our meeting. While this was reassuring to us it also made us jittery considering the huge responsibility we had to live up to.

The meeting started at 10:30am and we were surprised to see people other than the predominant tribe—Irulas—participating in the meeting. During the introduction, the Chennai floods became a handy reference for the effects of climate change, and climate variability and helped the participants relate to our study. Early on, one of the village elders put us on the spot and confronted us with the question: “What is it that we gain from this meeting?”. We had to patiently explain the premise of the project, the aims of the stakeholder engagement event, and detail how this research project was generating knowledge through a mutual learning process, which would hopefully result in policies being decided based on these local realities. The response seemed to have gone down well given that the participants were eager to participate after our explanations.

Johny Stephen takes one for the ATREE-ASSAR team and expounds on the uniqueness of the CARIAA-ASSAR approach to generating and using research (L to R: Johny Stephen, Milind Bunyan, Shrinivas Badiger, J. Revathi and Divya Solomon).

Although our first stakeholder meeting helped the team to better organise the second meeting, it appears each event brings a unique challenge. Our stakeholder event generated enough buzz to attract the attention of the intelligence sleuths of the local police! A few words in English from the always calm Shrinivas Badiger reassured the police and conveyed our benign intentions.

The highlight of our meeting was the two games that we conducted for the participants. The first one was ‘Chinese Whispers’ the difference here being that the message passed on was related to weather and agriculture. The message was completely distorted by the time it made it to the last person, much to the amusement of all present. This game helped expound the importance of accurate information, which plays a critical role in farming decisions.The second game involved ‘passing the ball’ with more balls being added progressively as the game proceeded; while the participants found this game entertaining, it also helped us communicate the concept of the additive influence of multiple stressors - climatic and non-climatic. Since the games were played in the afternoon it helped us and the participants overcome the dreaded post-lunch drowsiness.

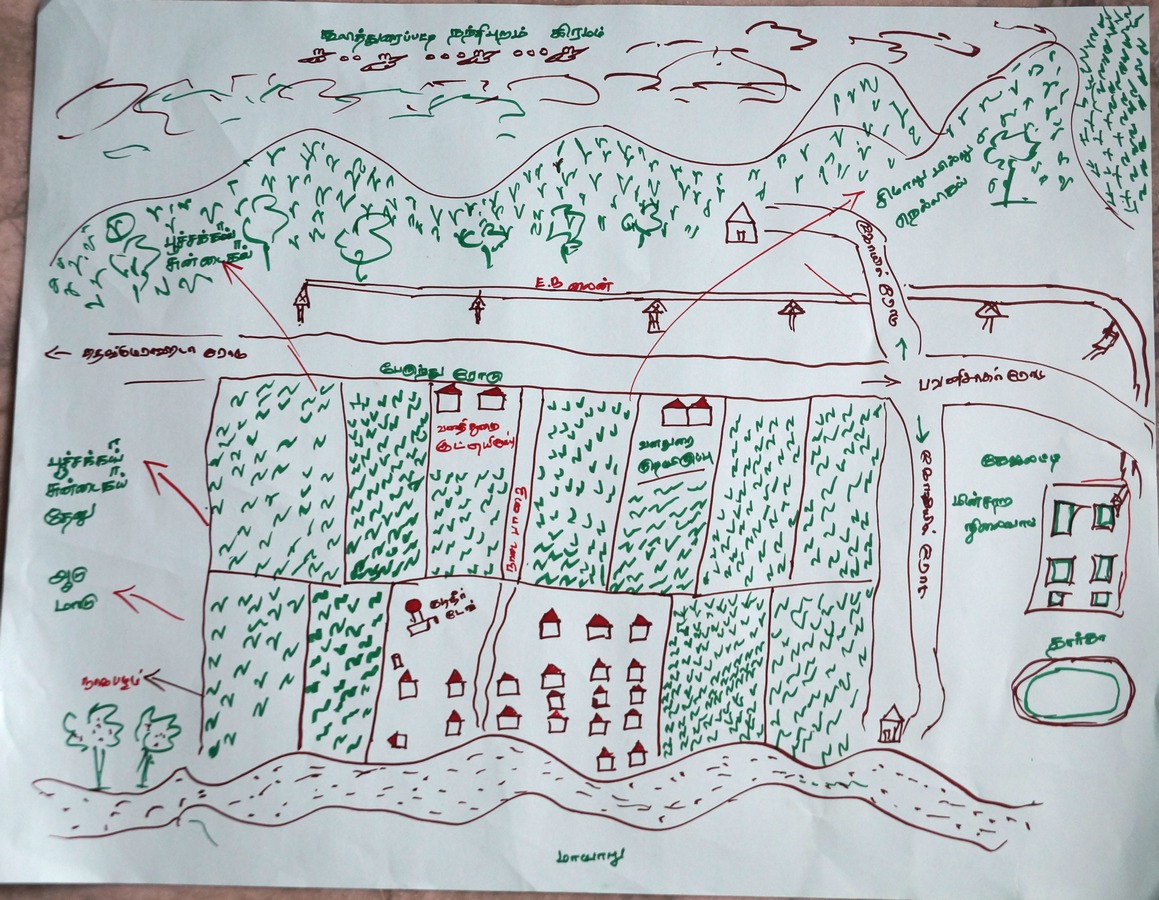

Following the outline from the previous stakeholder engagement event, we conducted sessions on resource mapping and cropping calendars. These exercises helped to give us a comprehensive view of resource availability in the region and farm management practises. Looking at these charts drawn by the participants, we realised that we had been able to gather much more information than in Bhavanisagar; hopefully we’re getting better at understanding our stakeholders!

The game of ‘Chinese Whispers’ in Tamil proves to be vastly entertaining and a great educational tool too.

Although this event was held for participants from the southern Moyar region who had similar livelihood profiles to the participants in the previous stakeholder workshop, subtle nuances in livelihood characteristics emerged. The villagers here also practised rain-fed agriculture; however they seemed to have less rainfall which could be attributed to the location of their villages in the rain-shadow of the Western Ghats. Two unique cases of irrigation were documented in the meeting. Gulituraipatti is a small village consisting of a closely-knit Irula community and irrigation water for this village is pumped from the adjoining Moyar River. The members of the community share the fuel and maintenance costs of the diesel pump. Thengumarahada is a much larger village in which land is primarily owned by the Badaga community. Here, farmers divert water from headwater streams for irrigating their fields. A formal body governed by the land owners of the region decide the share of irrigation based on the proximity of the field to the canal and the kind of crops being cultivated. Farmers are then advised to grow certain crops and, based on their adherence to these rules, irrigation priority is allocated. These two villages highlight the diversity of water governing practises in the region which have a resonating influence on farm management practises.

The resource map of Gulituraipatti as drawn by the villagers. Note the irrigated lands adjacent to the river (at the bottom of the map) and the drinking water storage tank in the top-left corner of the large settlement.

We wound up our stakeholder engagement event with a discussion on the recent changes in the community. Participants opined that the increased exposure to urban lifestyles has altered aspirations, with current generations preferring urban-based livelihoods. This ‘willingness to move’ to urban centres has been spurred on by an increasing demand for semi-skilled labour (particularly in the construction and clothing industries) coupled with decreasing agricultural productivity, and facilitated by the increasing mobility in the region. Villages located closer to the boundaries of the Sathyamangalam Tiger Reserve also have the option of working on construction sites in nearby villages, which serve as an efficient coping mechanism during the harder summer months and periods of drought. The long-term impacts of this seasonal migration on communities is, however, largely unstudied in this region.

Villagers from Pudhukad share a light moment with Revathi and Divya as they record the crop calendar of their village.

When multiple things happen simultaneously it makes us take a step back and wonder if these were just coincidences; the Chennai floods, the COP 21, our second stakeholder engagement event, all seemed connected. We need to ponder on the nature and the scale of these connections, even as prepare for our next set of engagements.