East Africa team's fieldtrip to Kenya's Kilimanjaro region

Written by Laura Camfield, David Loubser, Philip Lenaiyasa and Katrine Claassens

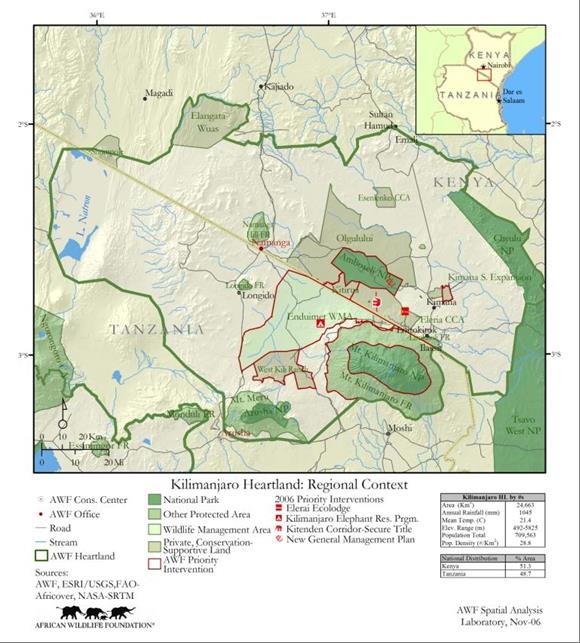

“Water issues, wildlife issues, people issues – it’s very complex,” comments Dave Loubser, a member of ASSAR’s East African team, on Kenya’s Kilimanjaro region. Indeed, problems surrounding water, wildlife and people frequently collide in this biologically diverse area of 23,000 km2. The landscape, mostly occupied by Maasai pastoralists, is characterised by a wide range of climatic and geographical features that provide an assortment of environments for the wildlife that inhabit it. While there are local projects in place to increase livelihood resilience and sustainability, difficulties regarding water availability, human-wildlife conflict, grazing management and governance structures undermine some of these efforts. In February, 2015 , ASSAR met with Kenyan stakeholders, including policy makers, NGOs and local government working on climate-change adaptation and with communities on the ground to hear about activities and priorities in-country at a range of levels.

Landscape and people

Local geological forces make the area’s ecosystem distinctive, productive and diverse, and give rise to habitats ranging from afromontane forests to woodlands, open savannah and aquatic habitats. Kilimanjaro forests discharge much of their annual rainfall to the plains below through underground aquifers that feed the many springs and swamps in the Amboseli basin. From Mt. Kilimanjaro and Mt. Meru, the landscape rolls to low-lying areas of semi-arid savannah in both Kenya and Tanzania. On the Kenyan side, the landscape’s most distinguishing features include: Amboseli National Park and seven large Maasai group ranches. On the Tanzanian side, distinguishing features include Kilimanjaro and Arusha National Parks, as well as Lake Natron and the low-lying savannahs of Longido.

The Kilimanjaro landscape contains great biological richness. Elephants, a keystone species, range widely from the montane forests to the low-lying plains across the international border. The elephant population totals about 1,500 individuals in Amboseli and the Longido area of Tanzania. There are also large populations of ungulates that use this landscape, migrating between wet and dry areas within and between the two countries. Two wards in Longido District (Tinga Tinga and Omolog) in Tanzania include wildlife-rich areas around Sinya and a corridor leading to Kilimanjaro. Lake Natron, a Ramsar site currently without any national protection status, provides important habitat for birds, namely flamingos.

Maasai pastoralists form the majority of the population with continuity of this community across the border. The dependence of pastoralism on space for livestock mobility, and tracking of seasonal resources, has also allowed wildlife to thrive. However, Maasai culture is dynamic and many households are adopting cultivation along swamps and on the slopes of the mountain. Additionally, the influx of non-Maasai people during the last three decades has increased the area under cultivation. In Kenya, in-migration has exacerbated pressure on Amboseli National Park, whilst in Tanzania cropland has increased at the expense of wooded and bushed grasslands. In Kenya, group ranches, a dominant land-tenure system and economic presence on the landscape, are under threat because government policy supports subdivision into individually owned parcels.

Highlights from the meetings

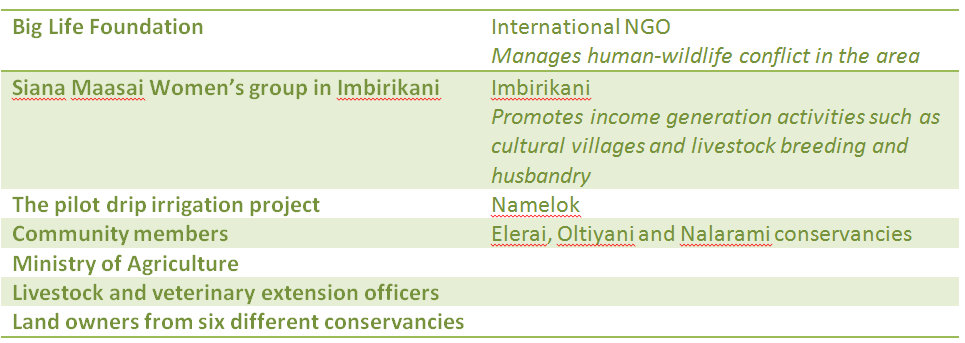

The focus of ASSAR’s East Africa team stakeholder engagement activities in this area was on organisations that interact with the African Wildlife Foundation (AWF), in activities ranging from rainwater harvesting to leasing land for conservancies. The team met with the following stakeholders:

While different stakeholders had particular foci, some overarching themes emerged which we briefly describe below:

Human-wildlife conflict

This was a particular focus of Big Life who reported that 13* elephants had been killed in the last year in the Kilimanjaro landscape. While poaching was a factor contributing to these elephant deaths, the main problem was water conflict between humans and elephants; previous initiatives to address this conflict had not been wholly successful due to the increase in agricultural development, which was spanning historical wildlife migration routes (‘corridors’). The revival of District Environmental Committees may provide a way of addressing some of these problems and this was a possibility raised by other stakeholders, e.g. officials from the Ministry of Agriculture. However, despite the existence of exemplary legislation, there are acknowledged weaknesses at the district and county governance levels which prevent its implementation and large financial interests due to the increase in land prices and profits to be gained from water-intensive activities such as horticulture and growing maize. Farmers at Namelok discussed the value of elephant proof fences to protect their crops, however, these are expensive to erect and require regular maintenance, which is not easy to organise collectively. There are also schemes run by AWF and Big Life that train rangers and provide compensation for livestock loss. These have been popular, but may not be sustainable, especially as more conservancy land is sold to private investors.

Image: Wildlife in the region

Water resource management

Farmers at Namelok and other places discussed problems of ‘water poaching’ and the costs of some of the new technologies (e.g. water storage pits, green houses, and the shift to drip irrigation rather than flood irrigation), which were designed to use water more sustainably. The technologies had had impressive effects (e.g. at the Kimana greenhouse project), but the costs were a deterrent and given that the technologies themselves are relatively simple, the team discussed ways in which they could be reproduced using local resources and labour rather than depending on expertise brought in from Nairobi. WRMA (Water Resource Management Authority) were perceived as not effectively enforcing regulation on illegal wells and water pumps, in part due to their operational dependence on Water Resources Users Associations (WRUAs) who were not trusted by the landowners the team spoke to.

Image: Lake Natron

Collective management of grazing

The Siana women’s group had enriched two areas of rangeland with great success, although due to Maasai cultural practices of food sharing they were not able to realise the financial value of their work (except as reflected in the quality of their own livestock). This was a problem faced by Elerai, Oltiyani and Nalarami conservancies who could not turn away migrant pastoralists and their herds, even though they recognised that due to the depreciation in quality of some of the rangelands their hospitality would not be reciprocated. Changes in the management of the rangelands, e.g. the move to elected officials, were showing some beneficial effects, and there seemed to be a greater appetite for holistic rangeland management which used zoning to ensure land was used appropriately (e.g. areas of grazing were given time to renew) and different uses were not in conflict.

Governance structures and the impact of devolution

The Ministry of Agriculture and WRMA officials talked passionately of the problems they faced accessing resources, including those to fund the administrative structures that would enable them to use these resources in a beneficial way (currently large parts of the budget remain unspent). They voiced the challenge of balancing multiple powerful governmental interests, such as those between the governor and Members of County Assembly (MCA) as well as the additional (and exacerbating) problem of the complex nature of governance structures.

Concluding points

The interviews provided a wide-ranging and vivid picture of problems in the area, however, the underpinning theme seemed water availability and the ways in which water and related resources are shared and managed. In this context, there is scope for ASSAR to follow up on promising and low cost interventions, such as community-led holistic grazing management, and exploring why the WRUAs are not working effectively in this context. Future stakeholder meetings should broaden the lens to look at education, health, opportunities outside agriculture - including in local towns, gender relations and relations with groups from different areas now farming in their communities, and the outcomes for the Maasai who have sold their land.

*this number was originally set at 100, but this was incorrect; we apologise for this information error.