Barriers and enablers to effective climate adaptation through the eyes of pastoral communities in Kenya

Written by Staline Kibet and Oliver Wasonga, edited by Lucia Scodanibbio

Experts are warning that livelihoods in Africa will be sensitive to future climate change and any increase in climate variability. This is particularly true in semi-arid regions, where precipitation is scanty and further warming will likely be devastating to livelihoods. In the absence of appropriate adaptation measures, productivity of these regions will drastically fall. The basic technology currently being used, as well as low incomes, means inhabitants of semi-arid regions will have few options to adapt.

The Adaptation at Scale in Semi-Arid Regions (ASSAR) project works at multiple scales to advance our understanding of adaptive livelihoods for vulnerable groups. In Kenya, our team investigated barriers and enablers for effective adaptation to climate change among agro-pastoralist and pastoralist communities in the semi-arid region of Isiolo, Meru, and Samburu counties of central Kenya. There, communities participated in Participatory Scenario Analysis (PSA) to gauge their level of preparedness, and assess possible options for adapting future increases in temperature. The PSA process focused on pasture scarcity, a key challenge for pastoral communities in the region.

We also investigated whether the Community Wildlife Conservancy (CWC) model, which is currently expanding steadily in the region, enhances adaptive capacity to declining water and pastures resources. To understand the CWC model, we used the multi-ethnic-owned Nasuulu Wildlife Conservancy, and the predominantly Samburu-owned Kalama Wildlife Conservancy, as case studies.

Borana and Samburu are predominantly pastoralists. Cattle, sheep and goats are their livestock of choice, although cattle were traditionally considered the main herd. Their grazing lands overlap at times, often triggering violent conflicts or negotiation during times of pasture scarcity. Due to the proximity of the two communities, their common livelihood strategy, and the shared landscape, we convened the communities in a forum to share their experiences and views on future options for adaptation.

Through financial support from START, on 13th September 2018, we organised a one-day workshop in Isiolo where 16 members of the Borana, Samburu, Somali, and Turkana communities participated. The workshop objective was to share knowledge on various innovations communities are adopting to increase their adaptive capacity to climate change impacts on livestock production and their environment, and how promising strategies can be scaled up and out.

Presentations involved plenary and group sessions, and were mainly based on participants’ experiences and recollections, often using local dialects and interpretation.

A member of the Borana community who had participated in the PSA, and later in peer-to-peer learning, started by presenting how the PSA was conducted, appreciating the community’s involvement in defining the statement of the problem and exploration of possible solutions. The approach of including the views from young men, young women, older men, and older women during the process, such as in the ranking of various scenarios, was recognised as inclusive and useful.

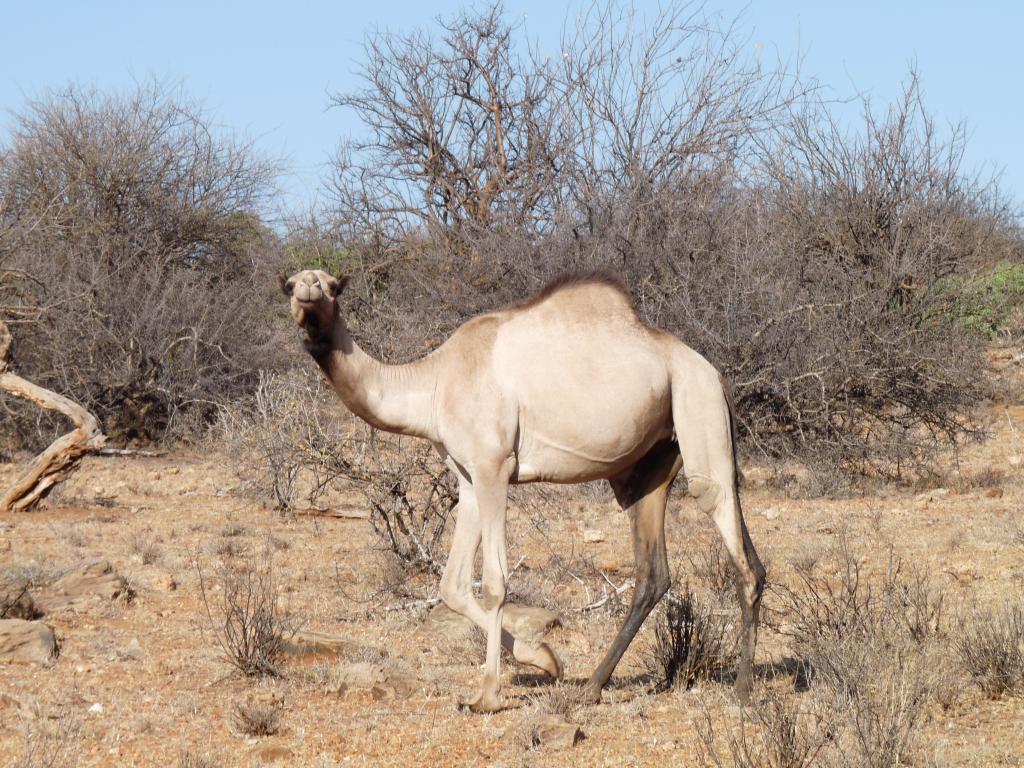

The four scenarios discussed during the PSA process were highlighted, and land zonation for various uses (grazing during dry, wet, and drought season), farming, and settlement found wider acceptance among the workshop participants. The second most-preferred scenario (replacement of grazers (cattle and sheep) with browsers (camels and goats)) generated lots of debate during the group sessions. Samburu community representatives disagreed with the strategy, due to their culture and traditions, as well as the perception that camels cause land degradation. A Samburu man who had raised camels for 20 years seemed convinced that they indeed degrade the environment: unlike cattle bomas/kraals where vegetation regenerates once abandoned, camel bomas may take years before any vegetation regerminates. Furthermore, the paths taken by camels to watering points often lack vegetation. He however acknowledged that camels are hardier, and survive better during droughts, providing milk when cattle are completely dry. Also, camels are a good investment as they fetch high prices in the market.

The group session concluded by discussing barriers and enablers to the two scenarios:

|

Enablers |

Barriers |

|---|---|

|

Land Zonation |

|

|

Better income generation |

Current severe land degradation |

|

Increase awareness (information dissemination) |

Resource conflicts and insecurity |

|

Training and peer-to-peer learning programmes |

Weak bylaws |

|

Existence of strong bylaws |

Poor land use and planning |

|

Mimic traditional heritage |

Rapid population growth (influx of people from other counties into Isiolo) |

|

Community cohesion and reduction of conflict |

Livestock pests and diseases |

|

|

Lack of political will |

|

Livestock diversification |

|

|

Capacity building (training) on this approach |

Rapid population growth (influx) and poverty |

|

Information dissemination |

Culture and tradition limiting communities to specific livestock species |

|

Social learning from other best practice |

Livestock pests and diseases |

|

Continuous availability of milk from camels |

Livestock rustling, camels easy target for thieves |

|

Camel keeping less labour-intensive than cattle |

Poor infrastructure (e.g., veterinary services, roads and markets) |

|

Tradition and culture of pastoralism |

|

On conservancies, the Samburu community credited the CWC model for: increased security among neighbouring communities; increased job opportunities for youth; improved social amenities such as schools, water and health facilities; and women and youth empowerment through micro-finance support to small businesses, and to increase inclusion in decision-making positions (see here for more). The presentation also indicated that the benefits of the CWC model were felt largely at the community level, with little trickle down to individuals and households, except in families where children benefitted from school bursaries and employment.

The Borana representatives rebutted by stating that: the model surrenders land management to foreigners; that arming the rangers with guns was responsible for increased inter-communal fights in the region; and that establishing CWC denies non-members access to their traditional grazing lands.

The group session thus discussed the strengths, weaknesses, opportunities and threats (SWOT) of the CWC model. Community ownership, empowerment and providing gender equality in leadership were noted as strengths. The model has an elaborate governance structure that is in part borrowed from traditional institutions. Through campaigns by the Kenya Wildlife Conservancies Association (KWCA) some supportive policies, such as community wildlife services, have been used to enhance the role of communities in wildlife management. Along with other proposed strategies, such initiatives may make CBC more responsive to the needs of the communities, as well as fulfil environmental and wildlife conservation goals.

Some weaknesses of the CWC model were also noted. Absence of membership identification documents make the model open to abuse, especially where democratic decisions are to be made by members. This leads to several challenges. For instance, bylaw non-compliance by some ‘members’ is a direct outcome of not having a register. It also complicates the sharing of benefits, and leads to biases during job allocation, especially in multi-ethnic-owned conservancies where everything is shared based on ethnic group size, and not on the actual number of members. Several conservancies still struggle with effective enforcement of set bylaws for the efficient running of the CWC model, with consequent conflicts over water and pasture resources. Finally, a number of CWCs are also strongly dependent on donors, as they are not able to generate enough resources to run their own affairs.

The CWC model offers several opportunities for expansion, however. The presence of picturesque scenery and abundant wildlife provides tourism opportunities for many conservancies in the semi-arid region of central Kenya. Recent expansion of infrastructure such as roads, communications, electricity, a planned resort city, and improved security in the region, bring in new opportunities as well as new challenges. Perhaps the biggest challenges are the potential loss of grazing land and land-use change. Conflicting interests among key and influential stakeholders, retrogressive politics, and misinformation or lack of information on the model, constitute some of the biggest threats to the CWC model. High illiteracy levels among the community members compound these challenges. Government’s inability to compensate pastoralists for loss of life, injuries, or loss of livestock to wildlife (currently running in millions of US dollars) makes the community wildlife conservation concept a hard sell.

While workshop participants agreed that CWCs enhance the capacity of communities to adapt to climate change, more is needed to enhance awareness on how the system works.

In conclusion, while cultural beliefs can be a barrier to effective adaptation – as communities do not easily adopt new “foreign concepts” – social learning is an effective route to impart new knowledge or skills. The recent rapid expansion of CWCs has largely been due to social learning from neighbours. However, political will is necessary to drive the effective adaptation agenda through formulation of supportive policies.

Community-led workshops were also found to be a great way to get people’s voices heard, particularly in the absence of national and county government officials, which allowed community members to express themselves more freely.